What should I read next? It’s a question we all ask ourselves time and again. Even with the countless essays, novels, screenplays, poems, and transmedia pieces to discover, to fall in love with or to detest, it can be a challenge to choose. Enter Expo Recommends, a curated selection of readings brought to you by the editors of Exposition Review.

Our 2019 annual issue submission season is well underway. For Vol. V our editors chose the theme “Act/Break” calling submitters to consider action, disruption, and the interstitial places in between. As we approach our guaranteed feedback deadline (November 1) and our official deadline (December 15), we want to give you, our readers, writers, submitters, and community, an extra dose of inspiration. So whether you read Expo Recommends for the recommendations or you want to get a leg up on the competition with a behind-the-scenes look into the preferences of our editorial team, we hope you’ll enjoy our “Act/Break” inspired Expo Recommends. And if you’re looking for a place to buy the books that supports local bookstores and yours truly with a 10% commission, shop our Bookshop.

Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers by Jake Skeets (Poetry)

From Poetry Editor CD Eskilson

I’m so excited about this issue’s theme because it’s essentially a statement of poetics. “Act/Break” so succinctly captures the foundational idea of a poem and that which separates it from being prose. It’s a statement on the nature of breath.

“Act” is the movement of a line or stanza; it’s the kinetic force that drives our reader to understanding. It’s how we say the thing. It’s the stream of gorgeous language that carries our image through the mind. “Break” is the opposing force. It’s the silence we employ to disrupt our readers’ notions, it’s the skillful caesura used to great effect. It’s the pause we let sit in a poem to say what can’t be said.

To me, the engagement with acting and breaking is what’s at the heart of every poem.

This dynamic is so masterfully displayed by Jake Skeets’s debut collection, Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers. This book is a beautiful, tragic journey through a landscape of erasure and silence, one wrought by centuries of violence against Native communities. Skeets’s quiet, nearly whispered poems transport us to Ná’nízhoozhí, also called Gallup, and have us nearly touching its trains, its buffalo grass, and its horse weed in our hands.

It’s through both the richness of Skeets’s rolling language and its rupture with white space and section breaks that these poems surround readers and take a hold of them. Each poem here is finely constructed in how it embodies the poet’s breath; it embodies both the act of speaking a place into being and silence of what cannot be said.

She Said by Jodi Kantor & Megan Twohey (Nonfiction)

From Nonfiction Editor Annlee Ellingson

Investigative journalism is by its very nature a feat of “Act/Break”—or, rather, “Break/Act,” wherein writers break a story that leads to some sort of act.

Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times reporters Jodie Kantor and Megan Twohey say as much in the final paragraphs of She Said, their riveting behind-the-scenes thriller recounting the research, writing, and publication of the story that exposed Harvey Weinstein’s decades of sexual misconduct.

What All the President’s Men was to Watergate, She Said is to the #MeToo movement, revealing the profound bravery of the women who shared stories of pain and shame—as subjects as well as writers and editors—that changed not only their lives but the lives of women everywhere, even when their harassers and abusers have avoided a Weinstein-grade takedown. (The book gives substantial ink to Christine Blasey Ford and her journey toward testifying against Supreme Court Justice nominee Brett Kavanaugh, who was confirmed anyway.)

Kantor and Twohey write with the matter-of-fact clarity of seasoned journalists, even referring to themselves in the third person to avoid confusion, with a rhythm—and a story—that takes root in one’s psyche.

“In our world of journalism, the story was the end, the result, the final product,” they write in She Said’s final pages. “But in the world at large, the emergence of new information was just the beginning—of conversation, action, change.”

Grief Is The Thing With Feathers by Max Porter (Experimental Narratives)

From Co-Editor-in-Chief Lauren Gorski

Grief Is The Thing With Feathers is a beautiful, lyrical, hybrid short novel that combines elements of folklore, fiction, and poetry to tell the story of a man dealing with the death of his wife while taking care of his two children. After the funeral, a giant crow (Grief) knocks on the door and moves in. The point of view shifts between the man, the crow, and the children—written more as poetry than prose. This is undoubtedly one of the most powerful things I’ve ever read that used the fewest words to achieve the gut-punch, and I’ll happily read it again and again to uncover new layers every time. This is what I want for “Act/Break”—hybrid forms that take risks and yet seamlessly thread together the pieces to make a whole.

Black Is the Body: Stories from My Grandmother’s Time, My Mother’s Time, and Mine by Emily Bernard (Nonfiction)

From Co-Editor-in-Chief Mellinda Hensley

Can I be honest with you, reader? I wasn’t always a fan of nonfiction. When I opened a book, I wanted to go elsewhere—to be transported somewhere outside the world I was used to. Into another time, another place. For me, nonfiction felt dry—fiction without an “oomph.”

Can I be honest with you, reader? I wasn’t always a fan of nonfiction. When I opened a book, I wanted to go elsewhere—to be transported somewhere outside the world I was used to. Into another time, another place. For me, nonfiction felt dry—fiction without an “oomph.”

Believe me when I tell you I was 100 percent wrong.

I found out in undergrad that nonfiction was just as able to transport me as fiction, but I was stepping into the skin of someone who was real. The weirdness, the joy, the heartbreak and suffering described—all of it was authentic and from the author’s point of view. And beyond that, as I continued reading, I found that nonfiction could also be porous—mixing and blending itself with what was and what might’ve been. What had the author recalled, how was it different? Did they grapple with the gaps in their own internal monologue? And how did their experience compare with that of others—just because it was nonfiction for someone, would it be true for everyone?

All these questions and more are grappled with beautifully in Emily Bernard’s essay collection, Black Is the Body: Stories from My Grandmother’s Time, My Mother’s Time, and Mine. After being stabbed by a stranger while she was in grad school at Yale, Bernard feels a freedom to examine herself as a writer, a patient, a black woman—all through her writing. She discusses her relationship with her parents and her white husband, her blackness and racism in America, the adoption of her children, her physical body and her body of work—even language itself. It’s a gorgeous work full of starts and stops, of backtracking and reconsideration; a shedding of old and new alike. I related to it as a woman, but still felt a necessary need to examine it as an outsider—I have never experienced racism, never felt the pain of being a mother, never been stabbed. Some of these were things I would never know personally, but the honest, visceral way that Bernard writes—it challenges me in all the ways fiction never could. This is a skin I’ll never be able to slip into, and frankly that’s the point. I won’t say anymore other than this: it’s beautiful, it’s elegant, it’s challenging, and it needs to be on your shelf.

Good Omens by Neil Gaiman & Terry Pratchett (Fiction)

From Fiction Editor Jessica June Rowe

By the Way, Meet Vera Stark by Lynn Nottage (Stageplay)

From Stage & Screen Editor Laura Rensing

With a theme like “Act/Break,” I could recommend anything from Antigone to Endgame and it would apply, but when it comes to plays that examine the balance between action and disruption, my very first thought was By the Way, Meet Vera Stark.

With a theme like “Act/Break,” I could recommend anything from Antigone to Endgame and it would apply, but when it comes to plays that examine the balance between action and disruption, my very first thought was By the Way, Meet Vera Stark.

Part screwball comedy, part social satire, and part bittersweet drama, Lynn Nottage’s play leaps through the decades, shucking off theatrical conventions faster than a chorus girl’s quickchange. Inspired by Theresa Harris, an African American actress who rose to fame in the 1930s and challenged Hollywood’s status quo for greater diversity and parts, the play follows Vera Stark’s humble beginnings as a maid, to her rise in film, to her mysterious disappearance in the 1970s as her star begins to fade.

Like Vera Stark, the play rejects what is traditionally accepted in theater and challenges the audience to adapt. The first half of her journey feels comfortable, a take on the screwball comedies of the 1930s as told through the eyes of Vera and her friends. The satire in the second act is much darker, as the setting shifts to 2003 and a group of amusingly pedantic academians dissect Vera’s legacy as a groundbreaking African American actress whose career was caged by racial stereotypes in Hollywood, and the burden of constantly playing “slaves with lines.” Though Lynn Nottage is better known for her Pulitzer winning dramas, I saw By the Way, Meet Vera Stark almost ten years ago, and it still sticks in my mind as an unforgettable mix of humor, heartbreak, and the importance of authentic, diverse representation.

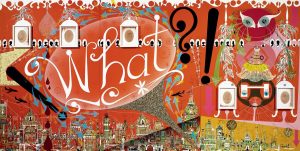

Lari Pittman: Declaration of Independence at Hammer Museum (Art Exhibition)

From Visual Art Editor Brianna J.L. Smyk

If you’ve read my past Expo Recommends, you know by now that I have something of a thing for art that incorporates language and text. So it’s no big surprise that my visual art Expo Recommends goes to the exhibition Lari Pittman: Declaration of Independence at Hammer Museum. An artist after a writer’s heart, Lari Pitmann starts his paintings with “words. Their sounds. Their meanings. Their inferred meanings. The complex cultural riddles an arrangement of words can evoke, the double entendres that can make a single word seem both clinical or risqué.” (Side note, for those of you who aren’t venturing to LA before January, or if you want to read an awesome piece of local journalism, check Carolina Miranda’s LA Times piece on Pittman here.)

Though his paintings begin with words, the colorful imagery and iconography spellbind viewers, inviting them to decode and understand Pittman’s visual narratives. Each work stands strong on its own, but in this retrospective, the collection of titles and the works themselves invite the viewer to uncover the cultural history depicted in Pittman’s oeuvre.

Pittman’s mix of English and Spanish text as well as his blurring of genre and mix of subjects—the works contain elements of surrealism, pop, and abstraction with commentaries on homosexuality, AIDS, love, sex, death, and art—position his art in an interstitial space, one that is representative of the work we publish in Expo and what I hope to read/see in our “Act/Break” submissions.

Now that you have some good writing inspiration and an insider’s look into our editors’ tastes, get reading, get writing, and get submitting to Vol. V “Act/Break” here.