What should I read next? It’s a question we all ask ourselves time and again. Even with the countless essays, novels, screenplays, poems, and transmedia pieces to discover, to fall in love with or to detest, it can be a challenge to choose. Enter Expo Recommends, a curated selection of readings brought to you by the editors of Exposition Review.

This month, some of the Expo editors give you recommendations inspired by our Vol. III annual issue theme, “Oribt.”

From now until December 15, Expo is accepting submissions for our annual issue in the theme of “Oribt.” This theme is about motion. It brings to mind celestial bodies and forces of nature as well as the familiar spheres and groves we inhabit in the world around us. It’s about tension and gravitational pull, whether from a planet, person, or idea. It draws you in and keeps you constant, but holds the promise of paving a new road and finding excitement and adventure.

This month’s Expo Recommends reflect the theme, and of course in true Expo form, the recommendations range in genre from fiction to nonfiction, screenplay to adapted novel, poetry to prose. Read on to find some amazing recommended readings and to get a little insight into the tastes of our editors—the ones reading your work and deciding what gets published in our lit journal. And don’t forget to send us your writing!

The Price of Salt by Patricia Highsmith and Carol by Phyllis Nagy (Fiction Novel and Screenplay)

From Art and Experimental Narratives Editor Brianna J.L. Smyk

Usually, it’s impossible to read and enjoy a book after seeing the movie adapted from the narrative, but for me Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt or Carol was a rare exception. I fell in love with the film Carol when I saw it in theaters. The movie, adapted from Highsmith’s novel, follows young shopgirl and amateur photographer, Therese (Rooney Mara), and an older, married woman, Carol (Cate Blanchett), as they meet, become intimately involved, and leave the men in their lives. It was such a complex yet simple love story, so subtle and powerful, almost understated but unceasingly bold. In particular, I was drawn to the pure love story—the reminder of “love is love” even before Lin Manuel Miranda’s 2016 Tony acceptance speech—which I found impressively timely, considering the progressive narrative was originally published in 1952, well before the gay rights movement began, and the film came out in 2015, following the Supreme Court’s rulings in favor of same sex marriage.

Usually, it’s impossible to read and enjoy a book after seeing the movie adapted from the narrative, but for me Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt or Carol was a rare exception. I fell in love with the film Carol when I saw it in theaters. The movie, adapted from Highsmith’s novel, follows young shopgirl and amateur photographer, Therese (Rooney Mara), and an older, married woman, Carol (Cate Blanchett), as they meet, become intimately involved, and leave the men in their lives. It was such a complex yet simple love story, so subtle and powerful, almost understated but unceasingly bold. In particular, I was drawn to the pure love story—the reminder of “love is love” even before Lin Manuel Miranda’s 2016 Tony acceptance speech—which I found impressively timely, considering the progressive narrative was originally published in 1952, well before the gay rights movement began, and the film came out in 2015, following the Supreme Court’s rulings in favor of same sex marriage.

When I had the chance to sit in on a lecture with Phyllis Nagy as part of USC’s MPW program, I jumped at the chance to read both the Nagy’s screenplay and Highsmith’s novel.

Though my recollection of reading the book and screenplay are largely dominated by Blanchett’s and Mara’s epic performances, I still get chills when I read or hear my favorite line from the book/screenplay/film, “Flung out of space,” which Carol says to Therese. It both addresses Carol’s opinion of Therese, a “strange girl,” and represents the way the two women spiral into each others’ lives and into love—not to mention, it fits these selections into Expo’s “Orbit” theme. The push-pull between the forceful attraction the women have for one another and the ways it repels them from their male counterparts drives the narratives, leading to the tense, dialogue-free moment—and poetic writing—that ends the story. The film, novel, and screenplay are all worth watching/reading for a comparative literature experience.

Though my recollection of reading the book and screenplay are largely dominated by Blanchett’s and Mara’s epic performances, I still get chills when I read or hear my favorite line from the book/screenplay/film, “Flung out of space,” which Carol says to Therese. It both addresses Carol’s opinion of Therese, a “strange girl,” and represents the way the two women spiral into each others’ lives and into love—not to mention, it fits these selections into Expo’s “Orbit” theme. The push-pull between the forceful attraction the women have for one another and the ways it repels them from their male counterparts drives the narratives, leading to the tense, dialogue-free moment—and poetic writing—that ends the story. The film, novel, and screenplay are all worth watching/reading for a comparative literature experience.

With the one of the distributors of this film now persona non grata in Hollywood due to recent sexual harassment allegations, the movie now also broaches an entirely different question of how we ingest art when the driving forces behind it—no mattter how small—skew our perceptions. But for me, any book, screenplay, or film that proves love is love, takes leaps for homosexuals, and gives voice to so many women, is worth watching—and discussing.

You Don’t Have To Say You Love Me by Sherman Alexie (Memoir/Hybrid)

From Editor-in-Chief Lauren Gorski

You may have heard of Sherman Alexie’s new memoir that came out this year, You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me, if only because of his heart wrenching Facebook post that went viral following the cancellation of his book tour. In his memoir, Alexie writes about losing his mother—and in the Facebook post he talks about her ghost. Both the memoir, and Alexie’s experiences afterward perfectly capture the theme “Orbit” when it comes to grief. Pain circles us. We keep returning to the same memories, the same lost opportunities, trying to convince ourselves that we are greater than our parts. But, even with his money and fame, Alexie realizes he is still the same kid on the rez, no better than his brothers or sisters who never left and maybe worse off for the stilted relationships he left behind. Alexie’s writing is powerful, as it has always been, but the way he weaves together his poetry with prose challenges the way we think about narrative. It can be raw. It can be nonlinear. It can’t always be healing.

You may have heard of Sherman Alexie’s new memoir that came out this year, You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me, if only because of his heart wrenching Facebook post that went viral following the cancellation of his book tour. In his memoir, Alexie writes about losing his mother—and in the Facebook post he talks about her ghost. Both the memoir, and Alexie’s experiences afterward perfectly capture the theme “Orbit” when it comes to grief. Pain circles us. We keep returning to the same memories, the same lost opportunities, trying to convince ourselves that we are greater than our parts. But, even with his money and fame, Alexie realizes he is still the same kid on the rez, no better than his brothers or sisters who never left and maybe worse off for the stilted relationships he left behind. Alexie’s writing is powerful, as it has always been, but the way he weaves together his poetry with prose challenges the way we think about narrative. It can be raw. It can be nonlinear. It can’t always be healing.

I was lucky enough to attend one of his last shows of his book tour, after the cancellation announcement. I remember Sherman Alexie standing on stage, breaking down in tears and griping, “I’m never writing nonfiction again.”

Sula by Toni Morrison (Fiction)

From Nonfiction Editor Annlee Ellingson

Toni Morrison’s second novel is called Sula, but it centers on two women, Sula and Nel, who meet in their dreams before they first play together as girls at Garfield Elementary School in Medallion, Ohio, or brave a gauntlet of leering men to get ice cream at Edna Finch’s Mellow House.

Toni Morrison’s second novel is called Sula, but it centers on two women, Sula and Nel, who meet in their dreams before they first play together as girls at Garfield Elementary School in Medallion, Ohio, or brave a gauntlet of leering men to get ice cream at Edna Finch’s Mellow House.

“So when they first met,” Morrison writes in her characteristically rich, evocative, pointed prose, “They felt the ease and comfort of old friends. Because each had discovered years before that they were neither white nor male, and that all freedom and triumph was forbidden to them, they had set about creating something else to be. Their meeting was fortunate, for it let them use each other to grow on.”

It is men and the women’s disparate relationships with them—Nel settles down and gets married, Sula spends her whole adult life casually sleeping around, including with Nel’s husband—that draw them together and push them apart, like the highly elliptical orbit of Halley’s Comet, swinging widely from inside Earth’s path around the Sun to outside Neptune’s and back again.

The pull of Sula and Nel’s relationship is so powerful that it affects the very mood of the town, which comes together in its support of one and hatred of the other, like the tides

And yet, in Morrison’s wrenching portrait of profound grief, through howls of sorrow and betrayal, Nel calls out for Sula, the girl from her dreams.

When We Were Romans by Matthew Kneale (Fiction)

From Editor-in-Chief Jessica Rowe

I picked this book off the shelf because it, like most new books I choose at random, had a pretty cover. On average I’d say about sixty percent of the time this strategy works out, and the contents of the book live up to the cover. When We Were Romans went above and beyond all expectations, however; nearly seven years after reading it, this book remains one of the first books that jumps to mind whenever I’m asked to recommend a new read. It’s a charming and heartbreaking story told from the point of view of a young English boy, Lawrence, who has moved to Rome with his mother and younger sister in the aftermath of his parent’s divorce. Lawrence is bright and observant, but still very much a child, struggling with this massive uprooting of his life, and the ever-growing feeling that something isn’t quite right. From his perspective we know not all is what it seems, but Lawrence himself is not mature enough to recognize it, let alone know what he can do about it. Instead, he throws himself into the support and defense of his struggling mother, with devastating results.

I picked this book off the shelf because it, like most new books I choose at random, had a pretty cover. On average I’d say about sixty percent of the time this strategy works out, and the contents of the book live up to the cover. When We Were Romans went above and beyond all expectations, however; nearly seven years after reading it, this book remains one of the first books that jumps to mind whenever I’m asked to recommend a new read. It’s a charming and heartbreaking story told from the point of view of a young English boy, Lawrence, who has moved to Rome with his mother and younger sister in the aftermath of his parent’s divorce. Lawrence is bright and observant, but still very much a child, struggling with this massive uprooting of his life, and the ever-growing feeling that something isn’t quite right. From his perspective we know not all is what it seems, but Lawrence himself is not mature enough to recognize it, let alone know what he can do about it. Instead, he throws himself into the support and defense of his struggling mother, with devastating results.

Matthew Kneale’s books are a master class in voice (see also: English Passengers, winner of the Whitbread Book of the Year and finalist for the Booker Prize), but When We Were Romans stands out for the dedication to Lawrence’s point of view, complete with musings and misspellings and stream-of-consciousness moments. The writing immerses you in Lawrence’s world and his unique observations on the city of Rome, but keeps you turning the page as you see how that world slowly but surely narrows, coming to revolve around the false truths that his mother has built.

The scope of his mother’s influence is only one of the reasons it’s such a perfect fit for our “Orbit”-themed recommendations. The narrative is also peppered with many asides from Lawrence about his favorite subjects, from ancient kings and Roman emperors, to astrological phenomenons like “the Great Attractor.” These stories work on multiple layers, providing comic relief and insight into Lawrence’s thought processes, and in many cases, reflecting his current situation. It’s often true that in life we gravitate towards interests that run parallel to our life experiences, even if we don’t always see the connection at first (if ever). And, if those connections are made, it can be painful to deal with situations that so drastically conflict with our world view. These conflicts can leave us feeling unmoored; like we’re on a course into uncharted territory, unsure where we stand or how we will ever come home again. When We Were Romans manages to subtly weave all those threads into a beautiful yet bittersweet whole.

The Oracle of Hollywood Boulevard by Dana Goodyear (Poetry)

From Associate Editor Channing Sargent

The wordplay in Dana Goodyear’s second book of poems, The Oracle of Hollywood Boulevard, is subtle and dark. The subject matter is Los Angeles and all of its incongruity. Pornography and sunsets, death and childbirth, femininity and hostility. The brief, distilled poems bleed with a hunger and yearning:

The wordplay in Dana Goodyear’s second book of poems, The Oracle of Hollywood Boulevard, is subtle and dark. The subject matter is Los Angeles and all of its incongruity. Pornography and sunsets, death and childbirth, femininity and hostility. The brief, distilled poems bleed with a hunger and yearning:

We want this.

The end to sleeping, the bittersweet

arousal, the peeling back, the soft bath

in resin, the release.

It’s writing of place:

I drive all day under a strike surface

scratched by skywriters’ mistakes, through the city

bleeding silver like a video game.

A thin book, it bulges with the imagery of an unknowable landscape. Just like Los Angeles, you’ll read it once and then go back to it over and over again.

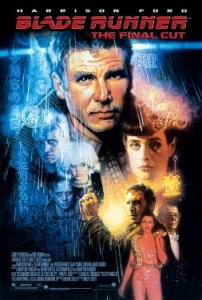

Blade Runner by Hampton Fancher (Screenplay)

From Stage & Screen Editor Mellinda Hensley

When I was a kid, I was introduced to the world of sci-fi through an anime show called Cowboy Bebop. It had space, bounty hunters, explosions, Corgis—everything eleven-year-old me wanted. And all of it was nestled in one of the most diverse worlds I’d ever seen on television. Even when I was young, I could tell that I was part of something big, a landmark in its own genre. And roughly a year ago, I remember feeling the same way when I went to see Blade Runner for the first time at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood. For those of you who haven’t seen it, the 1982 film takes place in the SUPER FUTURISITIC year of 2019 (I can’t tell if this makes me feel old or as though the world may end soon—maybe both). It follows the story of Rick Deckard, an ex-Blade Runner, who was assigned to tack down and eliminate “Replicants”; a type of humanistic android designed for slave labor. When four Replicants go rogue, Deckard is called out of retirement to track them down.

When I was a kid, I was introduced to the world of sci-fi through an anime show called Cowboy Bebop. It had space, bounty hunters, explosions, Corgis—everything eleven-year-old me wanted. And all of it was nestled in one of the most diverse worlds I’d ever seen on television. Even when I was young, I could tell that I was part of something big, a landmark in its own genre. And roughly a year ago, I remember feeling the same way when I went to see Blade Runner for the first time at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood. For those of you who haven’t seen it, the 1982 film takes place in the SUPER FUTURISITIC year of 2019 (I can’t tell if this makes me feel old or as though the world may end soon—maybe both). It follows the story of Rick Deckard, an ex-Blade Runner, who was assigned to tack down and eliminate “Replicants”; a type of humanistic android designed for slave labor. When four Replicants go rogue, Deckard is called out of retirement to track them down.

This film is a master class in world building, and I would highly recommend giving the shooting script a perusal once you’ve seen the film. It clearly defines all the aspects you need to know but keeps the environment just weird enough for your brain to feel uncomfortable. There’s an equal give and take here—a character serves the world, and the world serves the character, a similar balance I noticed in Cowboy Bebop. Blade Runner is a story that—although simple—is executed in a way that keeps the stakes high. Interrogation scenes are quick, biting, with a great undercurrent. It’s a script that makes you think about scenes as individual stand-alone sections that have wants and needs and obstacles all their own—i.e. every Replicant Deckard goes after could, in its own way, serve as an episode in a TV series, making it particularly useful to a short-form screenwriter like me. Believe it or not, I also learned that Blade Runner was a huge inspiration for Cowboy Bebop—Shinichirō Watanabe, the writer and director for Cowboy Bebop, was even asked to do an animated short film that acted as a precursor to the recent Blade Runner 2049. Nothing like coming full circle, right?

The shooting script for Blade Runner is available here.