What should I read next? It’s a question we all ask ourselves time and again. Even with the countless essays, novels, screenplays, poems, and transmedia pieces to discover, to fall in love with or to detest, it can be a challenge to choose. Enter Expo Recommends, a curated selection of readings brought to you by the editors of Exposition Review.

In honor of our call for submissions for our 2019 issue, Vol. IV: “Wonder”—which you should really submit to—this Expo Recommends features recommendations from our genre section editors and Co-Editors-in-Chief. Whether it gives you a leg up on the competition by knowing what we like, or it helps you find you next great read (or piece of art to ponder), enjoy!

My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh (Fiction)

From Fiction Editor Rebecca Luxton

It is my belief that wonder appears most where we don’t seek it.

I picked up what was widely hailed as “the book of the summer” feeling somewhat skeptical of a novel with high praise. What can I say, I’m a pessimist. Clearly I did not yet realize what author Ottessa Moshfegh, a veteran of The Paris Review and whose debut novel Eileen was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, had in store.

The story is a simple one: in My Year of Rest and Relaxation our narrator, immobilized by depression, goes from being disciplined at the chic art gallery where she works for sleeping in the supply closet to quitting her job (with a flamboyant gesture) and embarking on an unusual journey: to, for the next year—aided by pharmaceuticals—do nothing but sleep.

The book opens:

Whenever I woke up, night or day, I’d shuffle through the bright marble foyer of my building and go up the block and around the corner where there was a bodega that never closed. I’d get two large coffees with cream and six sugars each, chug the first one in the elevator on the way back up to my apartment, then sip the second one slowly while I watched movies and ate animal crackers and took trazodone and Ambien and Nembutal until I fell asleep again…

Emerging only to pick up pills and visit a wacky cat lady psychiatrist, she’s visited—incessantly, the narrator feels—by just one person, her best friend Reva. (“I loved Reva, but I didn’t like her anymore.”)

It is within the character of Reva, and what happens late in the novel, that the real wonder emerges: revealing itself all at once in a way I couldn’t possibly expect.

This hazy, dreamlike work is like sleepwalking through a strangely familiar story—one that is more than anything, native to the human experience.

Sunnyside by Glen David Gold (Fiction)

From Nonfiction Editor Annlee Ellingson

As the nonfiction editor at Exposition Review this year and last, I’m supposed to make a “wonder”-ful nonfiction recommendation in this space, and Glen David Gold’s Sunnyside isn’t that—nonfiction, I mean, for Gold’s books are both wonderful and full of wonder.

Like Carter Beats the Devil before it, Gold centers this doorstopper on a historical figure—here it’s Charlie Chaplin—and brings history to life with a riveting blend of fact and speculation. Never has a war bond tour been as thrilling as when it serves as the stage for an illicit kiss between then-secret lovers Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, orchestrated by the Little Tramp.

With his third book, I Will Be Complete—a memoir of his unconventional upbringing and his fraught relationship with his mother—Gold does write nonfiction. I’ll be reading that next along with Gold’s Flash 405 winners around the theme “Mystery.”

Revel in his detailed research into a couple of early-twentieth-century magicians—one literally, the other cinematically—in his tour-de-force novel.

Hera Lindsay Bird by Hera Lindsay Bird (Poetry)

From Poetry Editor Brian McGackin

This collection is excellent. I loved almost all of these poems. Hera Lindsay Bird writes in wondrous and magical ways that I wish I could, simultaneously bold & direct and mysterious & abstract. I always understand exactly what she’s saying and also not a word. She’s great, and the poems are great, and the book is great, and it made me happy. Also she’s from New Zealand, and how many Kiwi poets have you read?

Star Wars: A New Hope by George Lucas & A Quiet Place by Scott Beck and Brian Woods (Screenplays)

From Stage & Screen Editor Mellinda Hensley

From the get-go, I knew my wonder selection would be a difficult one to make. I initially had two scripts in mind—George Lucas’ ultimate journey of wonder, Star Wars: A New Hope, and the more recent creation from newcomers Scott Beck and Brian Woods, A Quiet Place. I loved both movies; they were original ideas that grabbed you with their premise and pulled you in throughout the movie, and beyond the rules of the world (staying silent in A Quiet Place) or the amazing visual effects (literally all of Star Wars), they both boiled down to stories about people—a family trying to live, a boy trying to find his destiny—they were intimate problems set on very big, sweeping stages. I couldn’t pick, so forget it, I’d recommend both.

From the get-go, I knew my wonder selection would be a difficult one to make. I initially had two scripts in mind—George Lucas’ ultimate journey of wonder, Star Wars: A New Hope, and the more recent creation from newcomers Scott Beck and Brian Woods, A Quiet Place. I loved both movies; they were original ideas that grabbed you with their premise and pulled you in throughout the movie, and beyond the rules of the world (staying silent in A Quiet Place) or the amazing visual effects (literally all of Star Wars), they both boiled down to stories about people—a family trying to live, a boy trying to find his destiny—they were intimate problems set on very big, sweeping stages. I couldn’t pick, so forget it, I’d recommend both.

And then I read both scripts.

What was ANY of this?

I’ll start with Star Wars. If you don’t know the plot or legacy of Star Wars, I envy you in some strange way—never before have you had to sit in on “who shot first” conversations or watch something beautiful be destroyed by a man who couldn’t let go of his own creation. But this is beside the point. Star Wars: A New Hope is a space opera that summarizes its problem in the opening crawl, so I’m not going to do it for you—go watch the movie. But as for the script, it’s massively different from the final product. I was astounded. How the hell did this end up as the movie I know and love? This, a script that cuts right in the middle of an opening epic space battle to a whiny teenager on a desert planetISWEARTOGOD (I have a lot of feelings right now, guys).

What resulted was a two-hour journey through the bowels of the Internet, a journey I very much recommend you take if you have the time. But for those who don’t and for the sake of brevity, I’ll say this: Maria Lucas, George Lucas’ wife, edited and saved this movie. If you’d like an explanation of how, this video basically tells you everything you need to know.

Now—A Quiet Place. Released this past year, the film is an apocalyptic story of monsters who have ravaged the Earth, killing humans in droves. The monsters are essentially blind, but have such acute hearing and ability to sense sound vibrations, they can find and destroy prey in a matter of seconds. A man and his family try to live their lives in this new silent but deadly world. The minute I left this movie, I wanted to get my hands on the script. I knew it had to be a little different—a ninety-minute movie where the characters barely said anything? What could that possibly look like on the page?

Now—A Quiet Place. Released this past year, the film is an apocalyptic story of monsters who have ravaged the Earth, killing humans in droves. The monsters are essentially blind, but have such acute hearing and ability to sense sound vibrations, they can find and destroy prey in a matter of seconds. A man and his family try to live their lives in this new silent but deadly world. The minute I left this movie, I wanted to get my hands on the script. I knew it had to be a little different—a ninety-minute movie where the characters barely said anything? What could that possibly look like on the page?

Oh boy. So, the script tops out at a breezy sixty-seven pages. Reading it is easy, quick, something you can do in about forty-five minutes. Like I previously mentioned, dialogue was scarce, so something had to take its place—I just didn’t expect those placeholders to be handwritten sections, wildly inconsistent spacing, actual photos and diagrams inserted right onto the pages, including, I kid you not, a scanned photo of a Monopoly board—namely, these are things things a screenwriter should avoid at all costs. I swear, this piece reads like something more experimental than stage & screen.

As with Star Wars, I turned to the Internet—what happened to this script? Namely this: John Krasinski, who both stars in and directs the film, wanted to develop the idea, but on the condition that he join the two original writers to substantially edit and rewrite sections of the script. It’s official: Jim Halpert saved this movie.

But at the end of the day, I still have to recommend both scripts for two very important reasons. One: editing is important. Without the brilliant help of some very skilled editors and outside writers, these scripts would’ve sat on a shelf for years, or would’ve been turned into terrible, clunky features. So accept now that as a writer, and especially as a screenwriter, people are going to edit your stuff. It’s important, it’s necessary, and though sometimes it can be maddening or frustrating, if you expect it, you can make those edits work in your favor and make sure that the idea you started with shines through. This leads me into reason two: editing is important, but the idea is paramount. Each of these scripts, awkward though they may be, still present an idea and a premise that’s captivating but engaging, original but couched in very human needs and wants. These ideas, the ones that present me with a thought I’ve never had, but built on a foundation of feelings I can recall at a moment’s notice—these are the pieces I’m looking for.

Just please avoid using any Monopoly boards.

You can read Star Wars: A New Hope here.

And A Quiet Place here.

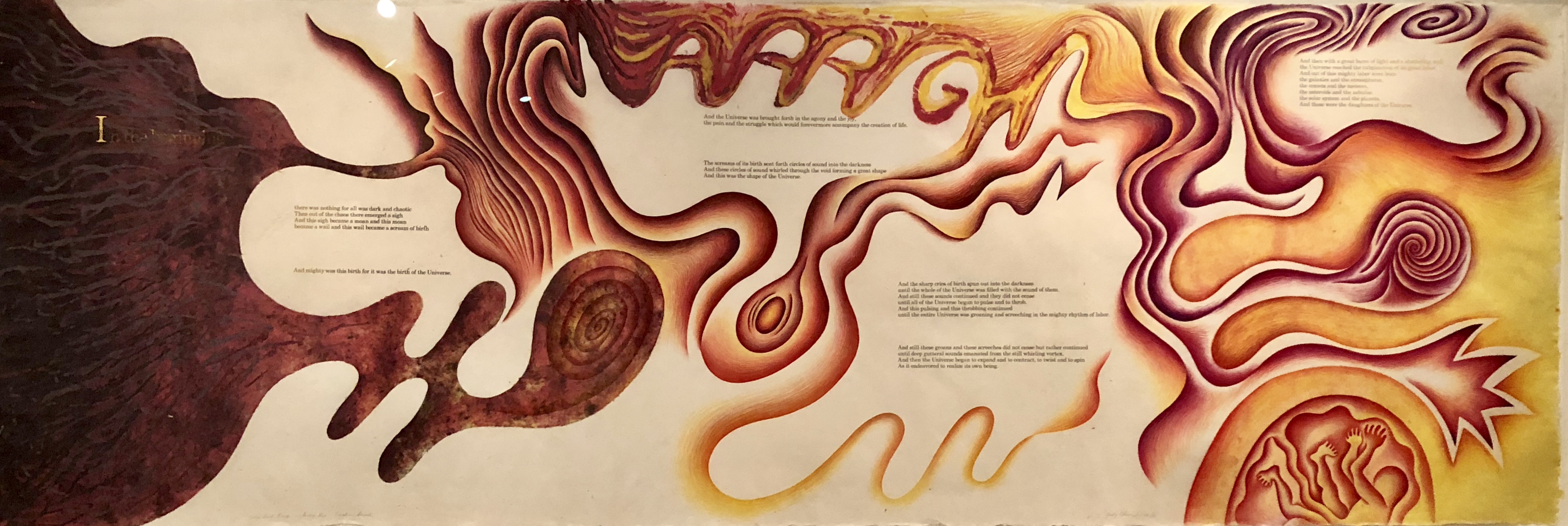

Creation Scroll III, 1981-1983 by Judy Chicago (Experimental Art)

From Art & Experimental Narratives Editor Brianna J.L. Smyk

You may remember from my past Expo Recommends, or be able to figure out by looking at some of our past issues, that I have a thing for text and art. We know, we know, Brianna, it combines your two passions, visual and literary art. But the piece I’m recommending caught me off guard. It was included in the final exhibition at the now-closed Pasadena Museum of California Art, where I had the pleasure of interning and then working on and off for almost a decade. It was part of Judy Chicago’s Birth Project: Born Again, an exhibition I worked on and was familiar with. Yet still, when I encountered the piece in person, I was overcome. Perhaps it is because it takes one of the best known first lines of a book, “In the beginning,” and turns it on its head. Or perhaps it is because it has to do with motherhood, both in the literal sense and the universal, which as a new mom and something of a cosmos nerd, both strike me. But the fluidity of the language mixing with the visual caused me to ponder—to wonder about—the creation myths engrained in our societies and those we create for new experiences everyday.

Since you can’t read the text, it begins:

In the beginning

there was nothing for all was dark and chaotic

Then out of the chaos there emerged a sigh

And this sigh became a moan and this moan

became a wail and this wail became a scream of birth

And mighty was this birth for it was the birth of the Universe.

And the Universe was brought forth in the agony and the joy,

the pain and the struggle which would forevermore accompany the creation of life.

The scream of its brith sent forth circles of sound into the darkness

And these circles of sound whirled through the void forming a great shape

And this was the shape of the Universe.

Seabiscuit by Laura Hillenbrand (Nonfiction)

From Co-Editor-in-Chief Lauren Gorski

Disclaimer: This reader is a horse person.

Disclaimer: This reader is a horse person.

Woolly by Ben Mezrich (Nonfiction)

From Co-Editor-in-Chief Jessica June Rowe

Woolly by Ben Mezrich is, in its own words, “the true story of the quest to revive history’s most iconic extinct creature”—and what’s more wondrous than bringing back the Woolly Mammoth?

Woolly by Ben Mezrich is, in its own words, “the true story of the quest to revive history’s most iconic extinct creature”—and what’s more wondrous than bringing back the Woolly Mammoth?

Even better, Woolly is just the kind of writing we love at Expo: a work of nonfiction that blends and borrows techniques of fiction to immediately invest the reader in the narrative. To start: chapter one is from the point of view of a baby Woolly Mammoth. Who doesn’t want to read about baby Mammoths?? In those first five pages I was confused, delighted, educated, and deeply upset. It was a fantastic start.

And let’s be real: bringing back the Woolly Mammoth just sounds cool. The Jurassic Park franchise is a big, bold, blockbuster lesson in genetic tampering gone wrong, yet the masses don’t show up to the sequels because of an interest in ethics: it’s the chance to see big, bold, brutal dinosaurs rendered in ever-more-realistic CGI. No matter how many parks those dinos destroy, there’s an inherent magic in the idea that we might one day have the chance to see a living, breathing prehistoric creature with our own eyes. It’s the reason I picked up Woolly in the first place.

Yet the de-extinction of the Mammoth isn’t about playing God, or science for science’s sake. And Mezrich’s Woolly does a great job of slowly transitioning a story of whos and hows into a journey of whys. There is a Pleistocene Park, but it was established two years before Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park hit the shelves, and its goal is lowering ground temperatures, not setting up concession stands. There are scientists “immortalizing” elephant cells to synthesize certain Mammoth traits, but in the process they’re curing a devastating epidemic among the Asian elephant population, too. Ultimately, this extraordinary revival is part of a larger story of environmental conservation and human survival.

Written in short chapters spread across multiple points of view, we get a wide range of perspectives on the scientific achievements—past, present, and future—that will make the return of the Woolly Mammoth possible. By utilizing a dramatized narrative style with re-created dialogue, Mezrich does a great job of bringing us closer to the key players: their motivations, challenges, and dreams for the future. It also makes the actual how parts, which are incredibly technical, much more accessible to those who might not have a PhD in biochemistry or genetic engineering. It can still get a bit tech-y at times, but it does pick up the pace as it goes and I love walking away from a book where I feel I learned something. Don’t skip the epilogue by leading geneticist George Church, which includes an actual transcribed Mammoth gene!

And if you’re wondering whether or not a Woolly Mammoth might be in our future… it’s not just possible. It’s inevitable. And it’s only the beginning.

“It’s all too easy to dismiss the future. People confuse what’s impossible today with what’s impossible tomorrow.” —George Church

Want to see your own work of wonder published? You can submit today to Exposition Review via Submittable–we’re accepting submissions through December 15, 2018!