by Kathryn Stam

Experimental

༄

Edible Letters: Use for Negation of Negative Thoughts Caused by Vow Infringement, Infectious Disease, and All Manner of Thievery

Your wisdom will blaze like fire!

Abstract — Based on translated 8-11 C. texts and informal participant-observation of contemporary cultural practices from Tibet, this article introduces the concept of edible letters and reviews their characteristics. The author shares details of her foray into tantric methods and methodologies, including the preparation and implementation of a happiness ritual outside of the typical field setting (such as Tibet and Nepal). Triangulation was accomplished through a balance of analysis of written documents, investigation of magical myths, and visualization related to letter swallowing.

Follow-up interviews were conducted with cultural experts (namely, shamans). The results of the study revealed that edible letters, although distasteful, are highly likely to have efficacy in the resolution of negative psychological states such as anguish and anxiety. In addition, it was found that the edible letter protocol described in this paper can be used for protecting oneself and all sentient beings from evil demons, knife wounds, drought, contagious fevers, and jealousy. They are also effective for winning arguments and finding peace in otherwise hollow or emotionally fraught moments of contemporary life.

Keywords — edible letters, gossip, transgressions, mind treasure, magic ink

* * *

1. Introduction

I ask you to understand why I write ceaselessly about the same few things, windswept Tibetan steppes I’ve never seen, and magic that I claim not to believe.

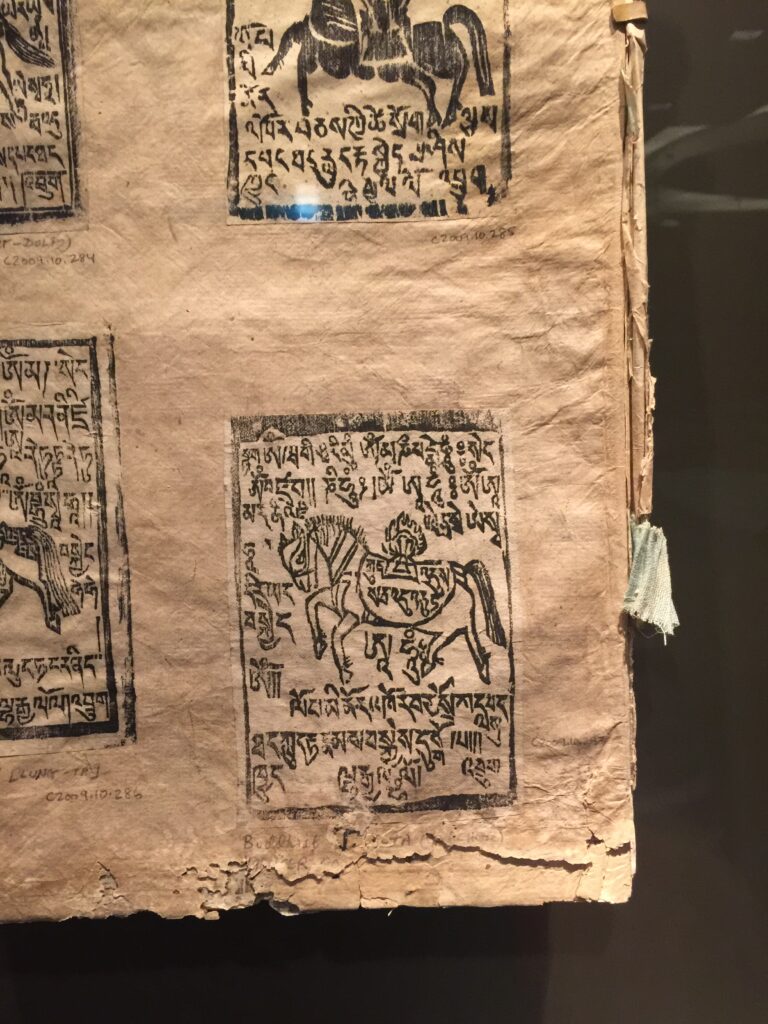

The term “edible letters” (also called “elixirs of wisdom”) refers to tantric letters written in herbal and magic ink, made of various local and extremely local (i.e., internal) ingredients. The amorphous figures start out as fluid, devoid of meaning, but then turn into Tibetan letters such as Ah, Bam, Dhi, Hum, Kam, Ram, Tam, Yam. The ancient priests taught village folk how to create the magic ink and empower the alphabet with their minds.

What is magical about the letters (yig) is the letters! (Garrett, 2009)

2. Background

Edible letters are good for the following scenarios:

When to the vows, infringement has befallen.

When to the woman, infertility has befallen.

When to the argument, loss has befallen.

When to a behind, a dog bite has befallen. (Sarkozi, 1999)

Eat [the edible letters] when your life is in danger.

Eat [them] when your head is dizzy.

Eat [them] when you have bad dreams.

Eat [them] when the earth quakes.

Eat [them] when gossip surrounds you.

Eat [them] in case of yellow fever.

Eat [them] to catch government officials and other robbers in their tracks! (Garrett, 2009)

3. Methods

I (the author) learn about the edible letters through extensive use of Interlibrary Loan. I read letters as pixels and gather timeworn poetry about demon-slaying like one might gather mustard flowers—seeing the blooms exploding toward the sun, knowing each one is unique, each one powerful and resonant. The ancient texts that were buried and later unearthed dance and sing their poetry. I print copies at the print shop and take the articles to bed with me, circling symbols and otherworldly instructions for inner peace.

I stumble across the edible letters in other ways too, once I am attuned to them. While visiting Nepal, my homestay brother Uttamdai wears a tantric amulet around his neck for protection, and, when I ask him, he tells me a bit about the edible letters, but says I’m not ready to know more about Tantra yet. My Nepali sister Menuka wears a necklace too, to get a baby faster, but she is shy to talk about it. Meanwhile, I want to infuse my memoir with magical energy that will make the reader tingle.

I Google Tibetan Bön and find a temple in Pittsburgh that is going to perform a chöd (ego-cutting) ritual. The public is invited, and so without even checking my calendar, I register and pay the $50 fee using PayPal. I drive to Pittsburgh. The next thing I know, I am lying down on a row of yoga mats with a group of fifty practitioners. As the drums beat and thigh-bone trumpets blow, we visualize ourselves cutting our bodies into pieces, feeding the hungry demons until satisfied. At first, the only Tibetan person there is the lama (teacher), and then a group of Bhutanese-Nepalis who come late and leave early. As a farewell, the lama hits me over the head and shoulders with a soft holy book. He tells me to study.

Closer to home in Rhinebeck, I go to a phurpa (devil’s dagger) compassion-building retreat and talk with more practitioners as we eat rice and curry, and brush our teeth together in the retreat center dormitories. Their responses to my questions surprise me. They are there to alleviate physical pain or illness. Their practice focuses on personal healing. They come to retreats to consult with their gurus: to have surgery or not, how to manage their back pain, how to manage depression. Some are there to fulfill promises they have made. Others want to help all sentient beings. Several practitioners brought phurpas to be blessed. I meet no one who had learned Tibetan.

Online, I start to watch live-streamed “cybersangha” sessions in which a well-known Bön monk in California teaches (in English) how to release anger, deal with negative emotions, and practice forgiveness. After chanting together in Tibetan (which I never learn how to do), Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche leads us in a guided meditation to a clear blue cloudless desert sky where we (the four hundred-plus people present from all over the world) give ourselves the gift of spaciousness, or “room to heal.” That time, I have visions of two people in my life who hurt me, and I bring the pain close as I am instructed. With my mind, I give the pain a warm hug like a mother would give a hurting child. With my eyes closed, I see the two pain-producers float away together on a puff of wind, and with them years of pain that I had been carrying like a loaded doko basket on my back, its head strap compressing my spine downward. When I stream the sessions from my phone, I tidy up the kitchen and listen to the mantras—healing through the sound of letters. The ancient and contemporary tango together in my house, my computer, and my dreams.

It’s August 2019. His Holiness Menri Trizin is doing his first North American teaching tour since becoming the new spiritual leader of Bön. I receive an email inviting me (as a former retreat attendee) to welcome His Holiness at Bön Shen Ling temple. I register right away, even though I had thought I was finished with the research for my book, tentatively titled 108 Ways to Slay an Enemy—in which I realize that my enemy is not the Thai man who was my husband, my ex, and the father of my son, nor his next wife whom I hated for twenty years, but myself.

When I pack my things for the retreat, I resist the impulse to bring along the Bön T-shirt that I got on Amazon for $20.85 with Prime free shipping. The design is square with geometric shapes in primary colors. At first glance, it wouldn’t be obvious that the rectangles form a left-facing swastika, meaning “eternal wellbeing.” I bring academic dress instead, and sweat in a cotton skirt as I stand in line to welcome His Holiness. There are about twenty other American women wearing Tibetan dress: fitted silky blouses and long skirts with aprons flowing down the front, with rainbow trim. The men—also middle-aged white people—are adorned in colorful yak-wool tunics. The Tibetan monks dress up a few men in full ceremonial garb—silk patches in primary colors—and give each of them an instrument: a long horn, a gyaling (Tibetan oboe), a cymbal, a drum. As the oldest monk puts on his pointed yellow Gelugpa cap, he says, “Don’t play them, though, if you don’t know how” (which none of them do). Another monk distributes Tibetan flags and tries to space out our line so it looks more impressive. We try to obey.

His Holiness arrives in a black Mercedes driven by the abbot of the temple. A young Tibetan woman is responsible for playing the processional song over her cell phone speaker, holding it up in the air like a prayer flag while His Holiness receives our greetings. We hold out white khata scarves (figure 1).

His Holiness takes the scarves and puts them over our heads, quickly, one by one, smiling as he goes. The monk at the rear wrangles us to follow him up the hill to the temple, past some chalk drawings (figure 2) and a pile of smoking juniper incense.

His Holiness stops at the temple porch and says a few words of thanks, then goes for a quick rest upstairs while we shuffle into the air-conditioned gompa (meditation room) to await his teachings. The healing mantras emerging from that room in Dutchess County are the same chants that echo across the Kathmandu Valley, the same sounds that vibrate from the throat of a silk weaver in Upper Mustang to the Kali Gandaki River and back over to Dolpo. Like mantras printed on the prayer flags (figure 3), the heart mantras A Kat Ah Me Dhu Tru Su Nap Po connect and heal those who chant and those who listen.

3.1. Research Questions

- Do the chanting sounds and the blessings from prayer wheels and printed flags intertwine or fly in parallel along the slipstream?

- Are the blessings that blow off of prayer flags edible? If so, in what way?

- Which negative emotions emerge when someone steals your husband? How would the author feel if she pierced her enemy with the antlers of a deer?

Giddy at the opportunity to meet His Holiness in person, I had requested one of the brief private meetings that His Holiness would grant to practitioners. I thought I would tell him about my book, but in the minutes I sit waiting in the hallway for him to finish with another person, my mind empties of intelligible thought and is replaced with insecurities. A tall Nyima monk asks me if I have a khata (scarf). I do not, so he gets one for me from a cardboard box in his room. I remove it from its plastic sleeve. Invited inside the room, I bow my head and present the khata, and His Holiness puts it over my head as a scarf. With my bad knees, I kneel on the rug in front of where His Holiness is sitting in a chair next to the abbot’s king-sized bed. The translator—another lama—paces next to him.

I tell them that I am writing a book about how Bön helped me to deal with negative emotions. His Holiness nods. I say it’s about letting go of anger. His Holiness nods. I show him the mock cover I had in mind—it is a photo of a tenth-century cave painting of a Bön monk, with a top hat (in which Bön priests wrapped their long dreadlocks) and fangs dripping with blood, and a left-turning yungdrung (swastika) to the side (Bellezza, 2017, 25). His Holiness gives me a sideways look. “Mmm,” he says. Through the translator, He says I should write the book, and He gives me his blessing. But the picture is not good for the cover. Not good for the front cover, not good for the back cover. “It’s okay … but it is not good for Bön,” he says, referring to the their reputation as black magicians and history of discrimination. “You can put the picture inside. No problem.”

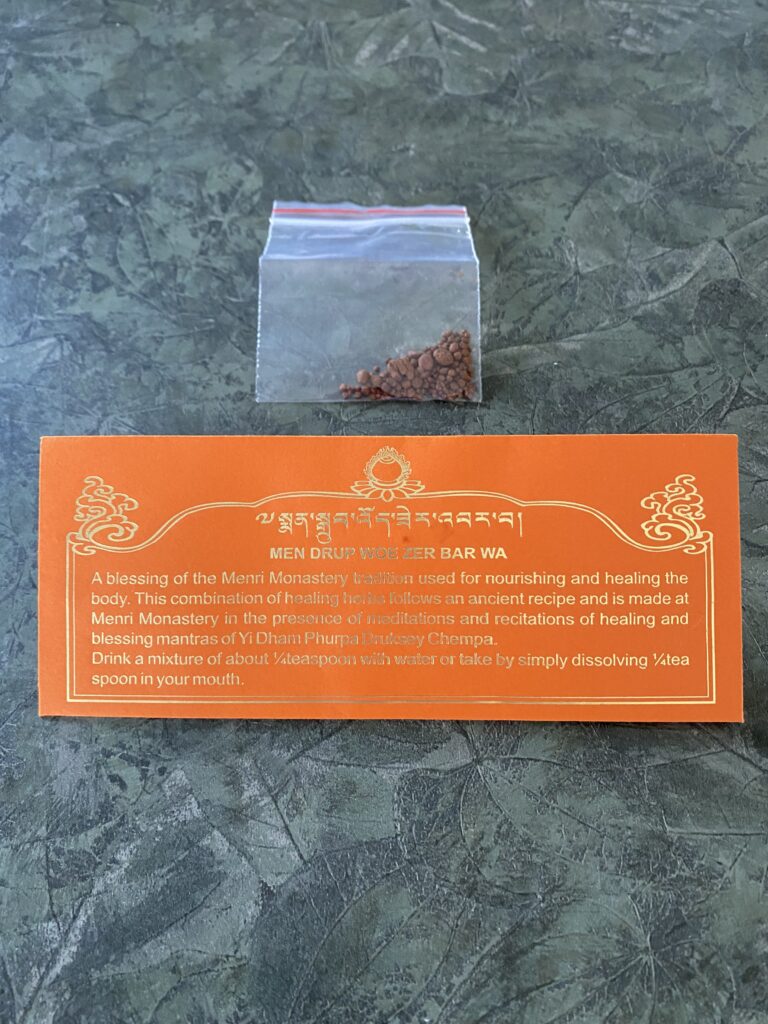

His Holiness gazes out the window. I tell Him how grateful I am to have met Him. He nods. I ask if there are any questions I can answer. His Holiness nods with a little smile, and says nothing. I can’t tell if he is bored or uncomfortable or neither. He reaches into a box and hands me two yellow protective cords and an eight-by-ten glossy picture of Sherab Gyeltsen, the founder of Menri monastery in India and abbot from 1405–1415. He says in Tibetan, “Stick to the real Bön, the texts. Not the rumors. Use the real thing,” and his translator smiles. “Only inside, okay?” “Okay,” I say. “Thank you, thank you.” I accept the gifts. I start to get up and he tells me to wait. I kneel back down on the rug while the translator goes into a closet and takes out a red envelope with Mendrup medicine inside (figure 4). His Holiness places it gently into my waiting hand and looks me in the eye for the first time. “Good,” he says. With another nod, I am dismissed. I get up and walk backward out of the room, bent in a pose of clumsy respect.

The next day’s teaching is on the Empowerment of Compassion, and His Holiness reminds us that we are all connected. The ambrosia that His Holiness pours is based on a recipe from old texts, and it was just prepared in the garage. The barley balls He consecrates and shares for us are connected all the way back to the founder of the religion, Tonpa Shenrap, 18,000 years ago. When His Holiness leaves the room, the practitioners who are able prostrate towards a thangka (Tibetan scroll painting) of Tonpa Shenrab. I stand there trying to be invisible.

After our group has received the first day of teachings, Chongtul Rinpoche says to me, “You are the luckiest person in the world. You cannot pay to get this kind of experience.” I think to myself, Well, I did pay for this experience. It was $475 for two nights at the Four Points Sheraton, all meals provided. But I know what he means.

When it’s time to leave, we have a special ceremony of dedication and thanks. We are asked to bring a khata and go up to His Holiness in a line. I am in the front row, so I am third. I choose a khata out of my bag that was given to me by a sweet huckster tour guide in Nepal who said it was blessed by the Dalai Lama. I am elated. It seems poetic to have a khata that was “double-blessed” by two Dalai Lamas of different sects.

As the line to the shrine shifts forward, I realize that we are supposed to drop the khata on a table in front of His Holiness, and that we’re supposed to leave it there. The khata that I covet is destined for burial under this growing pile of identical white scarves. Forty-seven more people stand in line behind me. They will drop their khatas on the pile. It will become a snowy mountain for His Holiness. I place mine on the table. It is buried.

Sitting back in my seat, I realize that even if I could reach forward and get my khata back, I would hardly be able to recognize which one it is. All of the khatas are blessed, but we are not getting them back. It doesn’t matter which one I brought back from Nepal. They are all the same. They are all blessed and none are blessed. Maybe it’s a fitting lesson: grasping leads to suffering, while letting go of grasping leads to profound and enduring wellbeing. Although some small part of me, for a few deep breaths into my belly, still wants my double-blessed khata back.

4. Materials

And now, let us bring back our focus to the concoction of edible letters, and how they connect to the author at this moment in time. I gently remind the reader that this sect of Buddhism, Bön, comes from the barley farmers, hunters, and shamans who lived in the foothills of the Himalayas a millennium ago and longer. From a monk who felt the teachings were threatened and so painted the recipes for the wisdom letters on rejak paper made from a poisonous root. From his auntie who helped roll and tie them into a scroll. From the helpers who hid the scroll libraries when invaders came. From the hill folk who lived generation after generation without knowing that the treasures were there, tucked into crevices in the rocky cliffs and shady valleys.

Here I snap my fingers and skip ahead six hundred years, or seven or eight hundred. To the bats whose smelly guano kept people from visiting the caves. To the rainbows that delivered signs when it was time to find the treasures. To the monks who established temples and libraries. To the scholars who learned how to read ancient Tibetan and translated the texts. To my librarian, Allison, who emailed me dozens of times to say, “An article you requested has been received. The article will be available for twenty-eight days from today; it will automatically be deleted after that. Please read, copy, or print the article before the deadline.”

The articles contain recipes for edible letters, and the methods for their use. Some ingredients for the recipes are no longer available or socially acceptable. Some are merely odiferous. The mixtures commonly contain “falcon blood and vulture meat, and less commonly vermillion, saffron, musk, and camphor, turmeric, cinnamon, frankincense, crystal, wood, or pig fat, … human flesh, [and] the bones of someone killed by lightning” (Garrett, 2009, 88).

Follow these instructions without deviation: Stop eating onions and garlic immediately. Store the letters in a clean jar. Rub the letters with the juices of a cow’s stomach. Mix the plants and other items into a paste for writing. Note that some of the “materials” are already pasty upon collection. Write the letters in [the collected] excrement (your own or that of others) mixed with the other ingredients from the recipe. Swallow the letters (on the tenth day of the waning moon) without touching any part with the teeth.

Write the letters.

Stack them vertically on a piece of paper.

Write in harmony with the victory star!

The letters must be written carefully, with no mistakes.

Roll them up and put them to your heart and hold the paper tight.

Eat the letters every day like food.

Eat them at noon and midnight.

Chant mantras. Imagine yourself as powerful!

You may go into the battlefield now.

5. Results

Participants who ate the edible letters and then visualized themselves holding a club and a noose were able to chase away bad spirits with their minds. Picturing themselves as dark blue and holding a bell resulted in success in subduing the aggressor. The subjects reported that using their minds to fill their bodies with five golden lights … as they swallowed the letters was found to be effective. For creating wisdom, the method of visualizing the letters as a shiny orange in color, and radiating outward was statistically significant, with p-values off the charts.

Participants ate the edible letters when their heads were confused. They ate the edible letters to return the curses to their owners. They ate the edible letters when their horses had diseases, and they had the horses eat them too. They ate the edible letters when they had the flu. They stuck the letters on tweens. They wore the letters in an amulet when a baby wouldn’t enter the belly. Then stuck the letters on their shoulders when the baby was finally coming.

Imagining the seed syllable at the heart and its light radiating outward, one participant became the syllable. Their wisdom blazed like fire!

Participants who did not eat edible letters or visualize themselves as the Tibetan letter A were still able to benefit from the ritual concept through a process we have named “Embracing the Metaphor.” Recalling their own role in thievery and betrayal was significant for the subjects in creating increased empathy and decreased levels of blood-boiling anger. In most cases, the targets of the participants’ wrath were unaffected by the treatment.

6. Discussion

The concept of “embodying the alphabet” that is presented here is interesting on several points. But if you did not already see that, I am not sure how else to explain. There seems to be a never-ending desire in human beings to fix problems, to find escape clauses, to discover the Fountain of Youth. While I reserve judgment on the efficacy of the ingredients presented in this article, I vouch for the process of continuing to learn things that grab hold of you and won’t let go. I state that Tibetan indigenous insights are applicable to real-life problems that we face in today’s society. One may argue that they are magic, that the ingredients are impossible (or unpleasant) to assemble. One might get lost in arguments about historical events. I choose to believe in the power of metaphors to release the mind from suffering. Statistical significance is irrelevant in this instance.

I heard some additional Buddhist wisdom today on Facebook, from that guy who asked Katie Perry for a divorce by text. What’s his name again? Russell Brand, whose expertise on the subject is not certified, yet it is pertinent here: Non-Buddhists say that when things are out of their control, they tend to worry. Buddhists say that when things are out of their control, why worry?

7. Further Study

They say it takes 10,000 hours to master a new skill or knowledge area. My calculations tell me that I may be getting close to investing that much time over the past five years. I have attended five retreats and spent approximately two thousand dollars, plus more on books, ritual objects, and the act of sponsoring prayers. And I would do it all over again if I had the chance. But you may agree that I have been a highly suspect narrator so please judge for yourself. I make no promises about the future. There is only here and now. The author plans to take a walk outside and bake some chocolate chip cookies using a browned butter recipe from Bon Appetit.

8. Conclusion

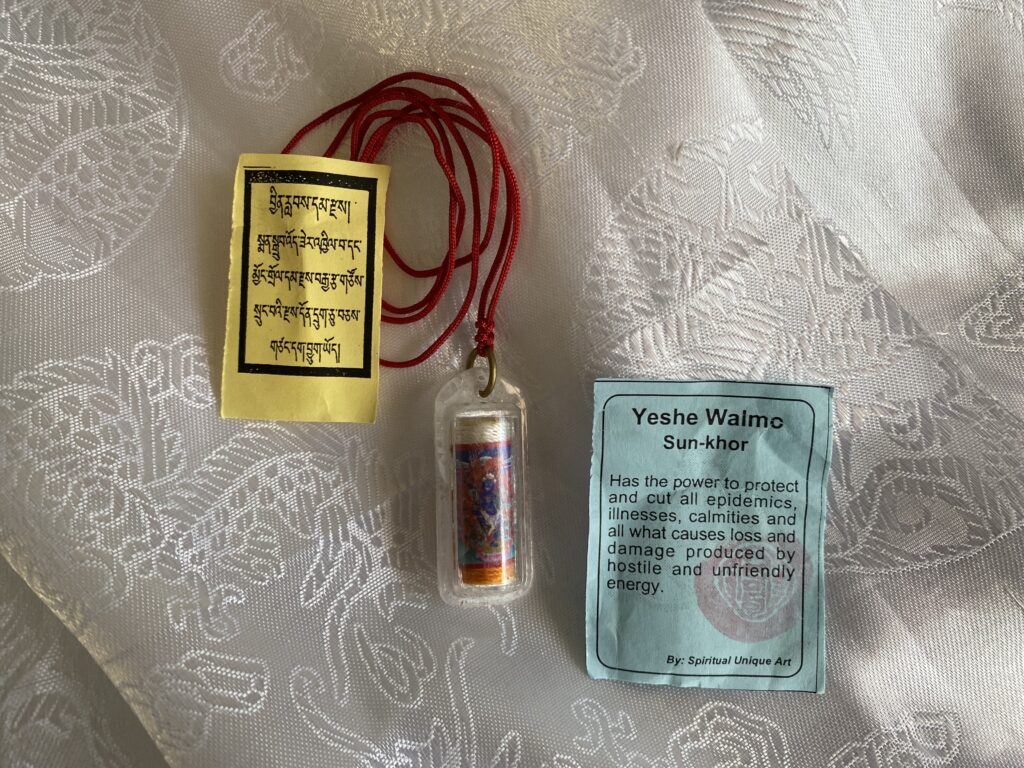

As I was finishing up this mock scholarly article, I received a precious packet in the post. It is a Bön amulet (figure 5), a plastic rolled-up image of the goddess Sipe Gyalmo.

The Queen of the World is in her wrathful form: blue with an angry face, Sipe Gyalmo wears a tiara of skulls and frightens the evil ones who intend harm. The amulet “has the power to protect and cut all epidemics, illnesses … produced by a hostile and unfriendly energy.” I wonder if it will protect me from well-meaning and hurtful criticism. I think of Amy Winehouse’s song lyrics, “I told you I was trouble. You know that I’m no good.”

The amulet packet came by FedEx, and with it arrived a healing mantra—Om A Bhi Ya Nak Po Be Sö So Ha—that should be chanted “one hundred, one thousand, or one hundred thousand times.” Obstacles, obliterated. The small treasure included DIY instructions: “Apply saffron to the front of clean Chinese paper. Write the seal of Sipe Gyalmo in the symbolic letters. … Tie this around the neck. It will be a supreme, universal protection from contagious illnesses” (Wood, 2020). It will protect as far as one or two “calling distances.” The protection may expand to 1,000 kilometers. May all beings benefit! “Your wisdom will blaze like fire.”

9. Epilogue

My mother has minor surgery tomorrow, a catheter ablation for her heart. I am tempted to make her wear the amulet, for safety from a contagious illness while she is in the hospital. But then I wouldn’t have it to wear to the grocery store, and to protect me from the myriad of other ill fates that could befall me. This week from his home in Queens, New York, Chongtul Rinpoche is offering the following to the goddess Sipe Gyalmo, Goddess of the Universe: 100 of red torma (barley balls), 100 candy items, 100 cookies, 100 apples, 100 oranges, 100 small nuts, 100 flowers, 100 banana, 100 glass[es] of wine, 100 candle light[s], and 100 incense [sticks]. The chong tsok (inner fire offering) ritual will help heal the small puncture in Mother Earth from which small poison winds are escaping and causing damage to the element of the earth’s lung (Bon Shen Ling, 3-28-2020).

I attend the first day’s Zoom session. Chongtul Rinpoche (2020) blows a conch and clangs a hand cymbal, and the screen freezes. Chongtul Rinpoche teaches about compassion from his temple in Queens, New York. Chongtul Rinpoche “returns” and says very quickly, his words having been stored up in a satellite, “The more times the mantra is recited, the faster the arrogant spirits will be defeated. We will all be protected from COVID-19.” As with a baby and the mother, the cry of the baby reaches the mother and the mother takes care of all solutions.

Note: The material that is italicized is not my original writing. It comes from the translations and explanations of edible letters from the Tibetan scholars and practitioners listed below.

* * *

References

Bellezza, John Vincent (2017). “The Swastika, Stepped Shrine, Priest, Horned Eagle, and Wild Yak Rider — Prominent antecedents of Yungdrung Bon figurative and symbolic traditions in the rock art of Upper Tibet.” Revue D’Etudes Tibetaines, 42, 5-38.

Bön Shen Ling (2020). Email to Practitioners from Chongtul Rinpoche. 3-26-2020.

Garrett, F. (2009/10). Eating Letters in the Tibetan Treasure Tradition. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 32 (1-2).

Sarkozi, Alice. (1999). The Magic of Writing- Edible Charms. Studia Orientalia 87, Helisinki. 227-234.

Wood, Raven Cypress (2020). Personal communication attached to Sipe Gyalmo protection amulet.

Kathryn Stam is a professor of cultural anthropology at the SUNY Polytechnic Institute in Utica, New York. Her fieldwork and other travels have taken her to Thailand, Laos, Nepal, South Africa, the Netherlands, Costa Rica, and Ireland. She is an advocate for resettled refugees. She is currently writing a memoir about culture and her experiences trying to communicate across cultures. Her creative nonfiction has appeared in Wanderlust, Griffel, The Write Launch, The Good Life Review, Flumes, Nowhere, and Santa Ana River Review.