by Gwen Goodkin

There I was, elbow-deep into hosting my eighteenth motherloving Pampered Chef® party, when I drew a line in the sand and walked straight out. My own house. Luanne was up there hawking the pizza stone again—always the frigging pizza stone, I mean these women all had the pizza stone. Try something new!—when I set down my serving tray and left the house. I must have walked for over an hour. I could not stop moving ‘til the anger grew small enough to stuff back in its cage.

The cars were all gone when I came back. All except hers. I exhaled, pinched the bridge of my nose, said, “Might as well get it over with.” Went inside like nothing, like I’d just stepped out to haul the trash.

“What in God’s green earth happened to you, May?” said Luanne. “I had to handle everything here by myself. The service, the pitch, the orders, the cleanup.”

“Luanne? My only response to that is: it’s about time.”

I will say, I could host the pants off a party. The kitchen was where I worked best, and Luanne knew it, which is why I hosted all the parties, and I’m talking all the parties. Even those Luanne was on the ticket to run, meaning she got paid, not me. My paltry take was a few free items I already owned, so I turned around and sold them at discount. Even then, it didn’t make up for the money spent on the party. As you may have already guessed, this dynamic had nowhere to go but *pop*.

Let me back up and fill you in. Luanne and I had been friends on and off for decades. On? Kids. Off? High school. On again? Kids in high school. Our daughters ended up twirling together as majorettes and became fast friends. Luanne and I had no choice but to sidestep back toward each other.

Childhood friendships are strange. There’s no wool to pull, because the person knows you, whether you like it or not. She understands what makes you great—why you were friends in the first place. She also remembers the unsavory bits. But, the happy part of reviving a lost friendship is that you push all those annoying traits aside. At first. Then the frustrations creep in, a little at a time, and you’re both back to being plain. old. you. Take me or toss me, you both eventually say, in so many words. Sometimes, that’s when the friendship truly begins. When you both no longer give a holy hoot. And sometimes that’s when the friendship breaks forever.

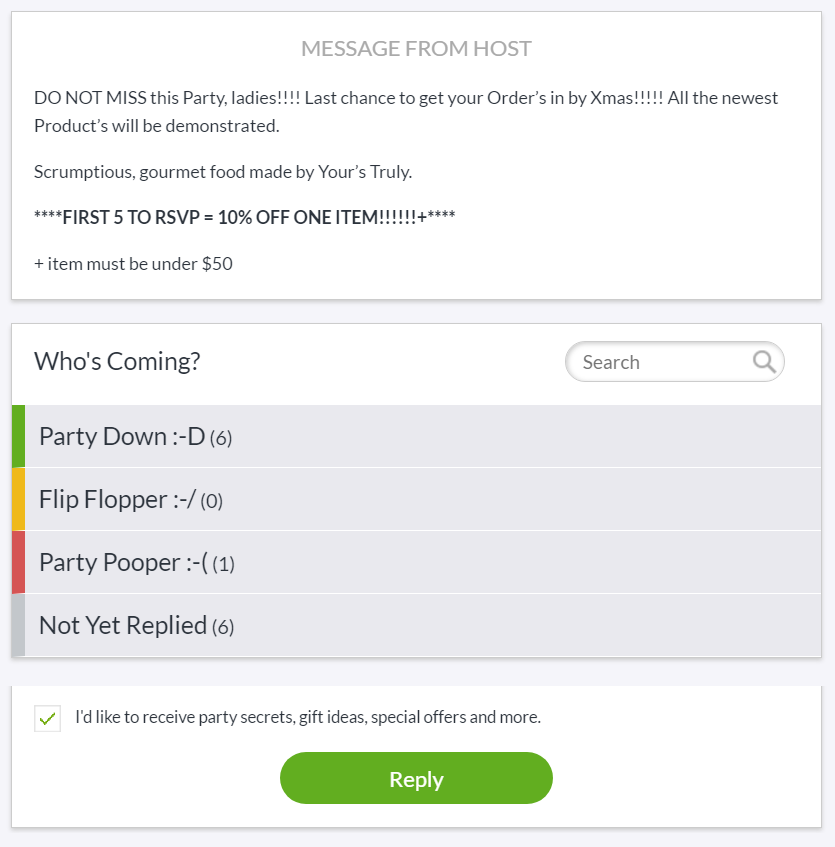

Can you indulge me for a minute? Would you just look at the invitation she sent?

(Click “Reply” to RSVP)

Where can I possibly start? I mean, are we German now, capitalizing nouns? The apostrophes. The font. The reply options. What really popped my cork, though, was the “gourmet food made by Your’s Truly.” First of all, everyone knows I’m the one cooking the food. That’s what they come for! Not the gadgets. No one wants them anymore. They want the dang free lunch! To top it all off, I’m an English teacher. Run the invitation by me, so I can at least proofread. And right there, I hit the nail on the head. That’s exactly why she didn’t want me to proof the invite. Because she didn’t want me correcting her. Because I graduated from college and she didn’t. Because somewhere along the line, we switched income brackets.

* * *

Oh, that May, I’d like to wring her goddamned neck for walking out on me in the middle of a party. Of course, she blamed her meltdown on me.

“You never help,” she whined. “I do everything and you take all the credit. And the money.”

“Oh, please,” I said. “Go lie to someone who’ll believe you.”

I’m sure she told anyone who’d listen that she was the one who threw all the parties, wah wah wah. And, in that she’s telling the truth. But she wanted to throw all the parties. Volunteered. So much so that I stopped asking and just slapped her address on the invite every time. Don’t be fooled, she puts on a good show. I have to be careful about how I present myself around town. I’m a teacher. I’m judged for what I do outside the classroom, too.

That’s what she wanted. To be judged. She wanted everyone to see her big, fancy house and decide that she was just as fancy. But there’s no fooling me. I know she came from dirt. I know everything.

May practically lived at my house as a kid. To the point where my parents joked about adopting her, and yet, it wasn’t far off. I went inside her house trailer exactly one time, when she was sick and my mom brought me over to deliver a meatloaf. My mom, always the class act, said she’d stay in the car while I ran the food in. Though I think Mom really wanted to see her, make sure she was okay. But she knew. It wasn’t her place.

Just as I left the car, Mom said, “I should have taken that meatloaf out of the pan and put it on a plate. That pan’s an heirloom, you know.” I agreed. The pan didn’t belong in that slump of a house. The aluminum was rusting from the ground up. The sides sagged. No driveway to speak of, just a few hops from the ditch. It looked like it fell off the side of a semi and was left for scrap.

I knocked on the door—barely—and saw May’s dad on the couch.

“Come in,” he said.

“Hi, Mr. Trame. My mom made some dinner for you.”

“Why?”

“Well, I guess because May’s sick.”

He swiped an inhale off his cigarette and pointed at the kitchen with his head. “Put it over there.” He wasn’t watching TV or doing anything, really, besides smoking.

“How’s May?” I asked.

“Same.”

“Okay, well. Goodbye.”

He nodded and I left, never so happy to get through a door in my whole life.

“How’s she look?” asked Mom.

“Sick,” I said.

“Well, of course, but—”

“She’ll be better soon. Her dad said thank you for the food.” Anything to get us off and away as fast as possible.

Mom looked relieved and started the car.

Not long after, May’s dad shot and killed her mom. We never got our pan back.

You would think that after everything that happened with May, what with her dad being in prison and all, she’d’ve grown quieter and more withdrawn at school. But no. It was just the opposite.

After she moved in with her aunt, her hair got bigger, her clothes brighter, her laugh louder.

“If I’m going to be the town cautionary tale, I might as well fucking embrace it.” She lit a cigarette for me. She’d convinced me no one would notice us out back behind the cafeteria dumpster. She was right. We went there every day at lunch. “Besides they all want to get close to me. Like I have a wild gene they want to be the first to discover, see if they recognize it in themselves.”

It was true, I’d been her only friend for years and now she had more friends than she knew what to do with. But I was the girl she talked to one-on-one. Everyone always wanted to find out where she went at lunch. She told them she walked home. Her aunt’s yard bordered the school parking lot. No one asked me where I went.

For the longest time, May had been my secret. Sure, we were friends, but I didn’t exactly announce it. She came over to my house and we kept a distance at school. But then, after the murder, our friendship flipped somehow, and I became her secret.

Me. A secret.

No, I’m not the type of girl anybody needs to hide.

“What’s that supposed to mean, it’s about time?”

“You know what exactly what I mean. Why am I the only one throwing the parties here?”

“Because you want to throw the parties. You want everyone to see your expensive furniture and your ‘custom’ house. ‘We built the house ourselves. It was a labor of love, but it was worth it.’ Barf.”

“You’re so transparent. Could you be any more jealous?”

I dropped a dish in the sink mid-scrub. What the hell did I care about cleaning up? “You wish I was jealous. At least I got my first choice for a husband. Unlike you, who reminds poor Roger every day he’ll never live up to the god who was Michael.”

“See, there you’re wrong. Michael was your first choice.”

“Until you stole him!”

“I didn’t steal him. He ran to me. Couldn’t wait to get away from you.”

“I was your only friend for years. Years! And what do you do to repay me? Steal my boyfriend.”

“He broke up with you. I didn’t steal him.”

“You did. You orchestrated the whole thing. And you know what else you stole? My mom’s loaf pan! That was an heirloom. My mom cooked, and I brought the food in to that hellhole, and you never thanked us and never returned the pan.”

“I have no clue what you’re talking about.”

“Yes, you do. You ate banana bread out of that pan all the time. It was green with scalloped edges!”

“Can you even hear yourself? You’re not making any sense. Take control.”

“Oh, I’m taking control. Right now. I don’t ever want to see your face again.”

“Good luck with that. We have a pair of majorettes, remember?”

“Even that you had to steal! I couldn’t be a majorette without you elbowing your way onto the squad. I’m going to twirl with fire! It’ll be a hit!”

“And there you were, being your usual bore self, wondering why you weren’t the star. Blubbering about Michael breaking up with you, twirling the same routine. Do something shocking! Amaze people!”

“Yeah, well, I’d rather be a good person than an entertaining one.”

“Maybe that’s your problem.”

“Maybe that’s yours.”

* * *

My whole adult life, I’ve driven the long route skirting town to avoid that trailer. It’s still there—boarded up, rotting from the inside out. But a couple months after my fight with Luanne, I got lost in thought and found myself fifty feet from it. I slammed on the brakes and vacillated between turning around or driving past. I finally decided I’d seen the place, what difference did it make to keep going?

And, can you believe, as I looked at that rusted dumpster of a house, my first thought wasn’t about my poor mom or my shitty dad, it was about that damn loaf pan? How the meatloaf had sat on our counter for days, festering, drawing flies. It was the pan that’d started the fight.

I was sick with mono, which in itself had set my dad off. “That’s the kissing sickness,” he said. “Who’d you kiss?”

“No one,” I said.

“You’re a bad liar,” he said. “At least you didn’t inherit that from your mom. She’s a world-class liar.” He ran a hand over his stubble. “Just don’t turn into a whore like her.”

I was in bed for days, didn’t even know Luanne had stopped in, when Mom came back after being gone for nearly a week. She up and left the second day I was terribly sick.

“I can’t take this anymore,” she said. “I was meant for bigger things than living on the side of a ditch.”

She came in like nothing, like she’d gone out for cigarettes and forgotten our address, and went right to the meatloaf. Dad sat on the couch smoking like he was blind and hadn’t seen her step through the door.

“Disgusting! Who the hell leaves meat on the counter to rot? Are those maggots?”

Dad jumped up and raged and the fight started, which was my cue to go to my room. I stared at a picture of myself in a fancy dress and white gloves and wished I was that girl. Then there was the gunshot and the smell of gunpowder and me alone with my mom while she bled to death, frantic.

“May. Baby. Help me.” The shaking started from her hands and moved up her arms. Her mouth turned white. That’s where death begins. In the lips.

“Always look smart, May,” my Aunt Helen said. We were crossing the street to the portrait studio. The fabric of our gloved hands grew hot from the friction of such a tight grip. “We’re outsiders in this town. A spinster and her orphan niece. So you must always look smart.”

Every year, from as far back as I could remember, Helen had taken me to sit for pictures. Before, it’d been a treat, getting dolled up in a pretty dress, but, after everything that happened with Mom and Dad, I didn’t want to look at pictures of myself. Before, the smile had been real, because I got to pretend for a day that I was the girl in the picture. A real smile on a pretend girl. But the pictures had become a chore because the smile was no longer real.

I had dragged my feet getting ready for the pictures. Earlier that day, I’d been exploring the creek with my friend Roger. He said he’d found worms the size of his thumb there and had caught a huge catfish with one. If Helen knew about the mud and the worms I’d never be able to see Roger again, so Roger and I rinsed our arms and legs at his house.

“Little May,” said the photographer. “Not so little anymore.” He bent to my height, licked his thumb and cleared a mud streak I’d missed from my hairline.

Michael died in a car accident. “Decapitated,” people whispered. A few weeks after the accident, Aunt Helen rushed into my bedroom before church.

“Get out of bed.” She scurried around the room picking up tissues and gathering clothes.

I hugged my pillow and hoped she’d leave.

“You’re a single mother now,” she said. “A threat.”

“What are you talking about?”

“You’re a threat to the women in this town. They’ll get ideas in their heads that you live solely to seduce their men.” She threw the pile of clothes into the hamper. “You’re a threat to men, too. They don’t like to see a woman making it on her own. They like to feel needed.”

I propped myself up on my pillows. Tiffany stood in the doorway in a blue ruffled dress. She had the smoothest blonde hair—so silky it often unwound when I tried to braid it. Helen had twisted it into two tight braids and bound them with ribbons.

It was Tiffany’s white gloves that got me out of bed.

We never had any kids, Roger and I. We tried. For a long time we tried, but it just didn’t happen. So we built the house instead.

I can’t help but feel I failed him. Some days I want to say, go off and find yourself a new wife. A younger one. Have a family. And other days I’m selfish and think, Don’t leave us. Not twice. We can’t be left twice. Tiffany calls him “Dad” and maybe that’s enough. He says I’m silly, that he’s perfectly happy with our daughter. See? He calls her “our daughter.” But I know there’s a place deep inside he won’t show me where the flame burns for a child of his own.

All of a sudden, I was in Luanne’s driveway. How’d I get there from the trailer? I had no memory of the drive. The garage was open; her truck was inside. I went to her front door. It had been a couple months since we spoke, and I was sure she’d slam the door in my face, if she even opened it at all. I rang the bell and moved to the corner where she couldn’t see me.

“What,” she said when she opened the door.

“I remember the loaf pan.”

“Good for you. Go get yourself a cookie.” She almost closed the door but I stopped her.

“The pan—it might still be in the trailer.”

“I don’t care about the goddamn pan.”

“Yes, you do.”

“It’s been twenty-five years. The pan’s long gone, May.”

“The trailer’s been boarded up ever since what happened. There’s a chance.”

She puffed a laugh. “That place would fall down on our heads as soon as we stepped inside.”

“Maybe,” I said. “Maybe not.”

“Why do you want me to go? Bring Roger.”

“I can’t bring Roger.”

“Oh, baloney.”

“You’re the only one.”

“The only one what?”

“Who’s seen that part of me.”

“So go show Roger.”

“I can’t.”

She folded her arms. “He’s your husband. Show him who you really are.”

“Okay,” I said. “But I need you to go with me first.”

“What—why am I even talking to you?” She flicked up her hands. “I’m mad at you.”

“Because you can’t help yourself. And neither can I. So let’s get this over with already.”

I turned and walked to my car. I was sure she’d follow me. She was too curious not to. I knew the pan was in there. I could feel its pull.

When we crawled through the kitchen window, we saw the pan still there, on its side, dropped like yesterday’s fortune. There was a chip where it came to rest on the ground during the argument all those years ago.

What I hadn’t expected to see was the studio portrait. Luanne found it in my old bedroom after shoving open the warped door. The photo was weather-damaged and had curled in on itself.

“Toss it,” I told Luanne when she showed it to me. But she tucked it in her purse, flattened it at home, and returned it to me in a silver frame.

Gwen Goodkin’s writing has been published by Fiction, Witness, The Dublin Review, The Carolina Quarterly, Atticus Review, jmww, The Rumpus, Reed Magazine, and others. She has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and has won the Black Fox Literary Magazine Contest as well as the John Steinbeck Award for Fiction. She lives in Encinitas, just north of San Diego.